They call it Music’s Biggest Night, but it’s also the most watched annual non-sports live event on television, making the Grammy Awards perhaps the ultimate showcase for audio, video, lighting and wireless techniques. [related]

So where better to turn for insight into those categories than the Grammy Awards technicians who supervise and operate them, under the watchful eyes (and ears) of the music industry’s one percent and about 20 million viewers worldwide?

Most of the folks who keep the Grammy Awards loud, lit, and running smoothly have been on the show’s production team for decades.

Michael Abbott, its audio supervisor, has been performing that role for 30 years, starting out when the award for Song of the Year went to Bobby McFerrin for Don’t Worry, Be Happy.

The event took place at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, a few miles and a million beats from the cavernous Staples Center in downtown, which is better known by its hipster moniker, DTLA.

That’s where the Grammy Awards technicians — who are also regulars for the Academy Awards, the CMAs, the ACMs, the Tonys and most of the other major awards-show broadcasts — have been doing the show from for the last 19 years.

Here, four Grammy Awards technicians tell us what this iconic American show can mean for any major live event’s production.

Sound Tech at the Grammys

Pre-planning and volume control are two key elements to an event’s live sound that can impact its overall effectiveness and experience, says Ron Reaves, who this year mixed the music inside the Staples Center at his 17th Grammy Awards show.

When confronted by a wide array of music styles and genres, taking good notes ahead of time is critical.

“I show up at the Grammy awards with a pre-built console file that has everything in it that I can imagine dealing with at that show,” he explains.

“I spend the first day on site programming snapshots in the audio console for each musical act. These snapshots will typically change a bit as we go through rehearsals, but for the most part the information is accurate.

“I use a lot of channel pre-sets, and when I write a snapshot, it’s EQ’ed, compressed, bussed and panned ahead of time. I find that 80 percent of the time I don’t have to change stuff very much, just raise the faders.

“A big part of our success at that show is that we can get it together quickly, and we can adapt to any last-minute changes or disruptions easier, all as a result of that pre-planning.”

— Volume is often the real challenge when it comes to making live music work in the context of a big event

Reaves also keeps an eye and ear on the volume, watching the decibel meters on the console and on his iPhone, but also listening for imbalances in the live sound that can occur as the SPL in the house begins to creep up.

“You want to watch across the frequency spectrum so that you’re getting the right tonal balance as well as the right mix of instruments and vocals,” he explains. “An imbalance of one is as bad as the other.”

But volume is often the real challenge for Grammy Awards technicians when it comes to making live music work in the context of a big corporate or other event, where the music might be a major attraction but is still there to support an event’s larger purpose, such as a new-product introduction.

“The trick for live music in a larger event, especially one that has a broadcast or streaming component, is to keep the level loud enough so that there’s a good degree of excitement in the venue, but not so loud as to overtake the message,” he says.

Some of the ways to keep the music in the hall but not to let it overcome a live broadcast or stream is to use close miking of instruments and amplifiers. That helps keep the music inside the PA system where the FOH mixer can control it, and not let the sound from the stage dictate the level in the room.

“At the Grammy Awards, I’m mixing the live sound for the artists on stage who are up for awards, but their performance is focused for the broadcast,” Reaves explains.

“My real job is to keep the excitement level of the audience up, so viewers at home can hear them and their applause and cheering, which is part of what makes the entire event work. Make that the focus of the mix for an event. It’s that simple.”

Grammy Awards Technicians Choose Wireless

One would have been excused for doing a double take at the wireless-audio command center in the Staples Center, just behind the main runway to the stage.

There, wireless microphones from Shure, Sennheiser and Audio-Technica were nestled together in a series of metal meatloaf trays, the kind you can pick up for $1.99 at Wal-Mart. But what was cooking was way more critical than some meatloaf.

As the number of wireless microphone channels used at awards shows and live-event productions in general has steadily increased, the potential for interference among them has also risen.

There were about 40 channels of wireless microphones at this year’s show, plus another 28 channels of wireless in-ear monitors and 15 channels of wireless for instruments on stage.

It’s known as intermodulation (IM), and can occur when multiple wireless mics (or any kind of transmitters) come close enough to “talk” to each other, as their receivers look for the strongest nearby signals.

The signal from each transmitter generates IM in the output stage of the other. These new signals are transmitted along with the original signals and can be picked up by receivers operating at the corresponding frequencies.

They can also create new frequencies, products mathematically related to the original transmitter frequencies that consist of sums and differences of the original frequencies, multiples of the original frequencies, and sums and differences of the multiples.

It’s like high-school algebra on steroids, but it can seriously complicate the most fundamental task in RF in the wake of the FCC-mandated RF reallocation completed last year: frequency coordination.

Why Meatloaf Trays?

That’s where the meatloaf trays come into play. With some foam glued inside them to cushion the mics as they are moved to and from the stage, the metal baskets help keep the transmitters isolated from each other, helping to avoid IM and the frequency mayhem that can follow on large shows.

“Newer digital wireless microphone systems aren’t as prone to intermod issues as older analog ones were, but it’s still prudent to keep wireless microphones isolated from each other as much as possible,” says Steve Vaughn, a principal in Soundtronics Wireless, which manages the wireless microphone contingent for the Grammy, Oscar and other major awards shows.

“Other important things for wireless management include having a good frequency plan that has been verified with a spectrum analyzer. Another is a robust antenna system with multiple zones. And when the show is over and you can always take an isolation tray and make a savory meatloaf or sweet banana nut bread.”

Grammy Awards Backdrops are Stressful

You may have noticed that backdrops increasingly consist of LED or projection instead of, or in addition to, conventional scenic materials.

That’s added lots more creative latitude for live and broadcast productions, but it also creates more potential for what John Pritchett, the technical supervisor on the Grammy Awards show, calls “the single biggest issue for video” — frame-rate synchronization.

Simply put, if all of the video elements of a production aren’t dialed-in to the same frame rate, artifacts such as flickering can occur, turning what was supposed to be a backdrop into a distraction.

“LED screens are everywhere now, and everyone wants them or large projection screens on stage,” says Pritchett. “That sets up the potential for artifacts like flicker to take the attention away from where it’s supposed to be, on stage and in the picture.”

— The single biggest issue for video: frame-rate synchronization

The solution is to coordinate the frame rate to be used for all video elements well before the event itself, choosing based on what the broadcast or other transport vendor will be using (various broadcast networks use either 720 or 1080 lines of resolution, and either interlaced or progressive iterations of them, which will determine frame rates), or else what the various video participants decide on.

That, Pritchett emphasizes, must also include the content providers, who will be sending video to screens that may also be showing live video.

“Everything has to be gen-locked together, from a single frame-rate generator source,” he says.

At times, that may require some ingenuity from Grammy Awards technicians. For last year’s Emmy Awards show on NBC, the network’s 1080i broadcast had to accommodate a 120-foot-wide projection screen used as the backdrop on stage.

Due to how interlaced video processes picture at two lines per frame at 29.97 fps, close-ups of those on stage might have included distracting artifacts when the projection backdrop was also visible in the picture.

Instead, Grammy Awards technicians decided to have all video elements synchronized to 1080p (progressive), which would handle the close-up shots better due to its higher frame rate (59.94 fps) and then convert the entire broadcast to 1080i for home viewing.

“Those watching the video in the venue saw a great experience on stage and on the venue’s screens, and it was just as seamless for home viewers,” says Pritchett. “The key to making video work for complex events that use a lot of LED and projection is to coordinate frame rates a early as possible.”

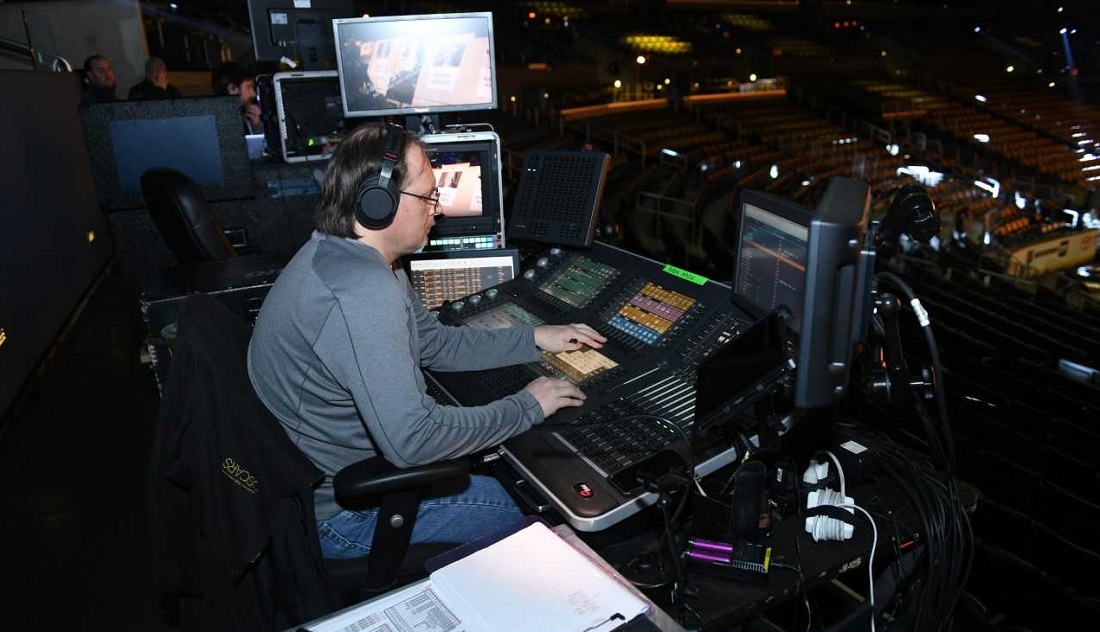

How Grammy Awards Technicians Light it Up

Lighting the Grammy Awards show is as much a logistical challenge as it is a technical and creative one for Grammy Awards technicians, says Noah Mitz, co-lighting designer on the show along with Bob Dickinson.

One way to achieve a good outcome under the kind of time constraints that come with the this event is to divide the lighting programming tasks among more operators.

At the Grammys, for instance, three lighting programmers cover the audience, the main stage and set, and the individual performances; a fourth team member is dedicated to managing the media server operation.

“When you’re crunched for time, a division of labor can make all the difference,” he says, adding that the cost of an additional crewmember can be more than offset by an outcome that looks as good in the seats as it does on the screen.

“We take this approach for other shows, too, like America’s Got Talent, but it can applied to any live-event production.”

Like other aspects of the telecast, lighting is designed around making what goes to air look great, but it also has to make the in-venue experience as good as possible, as well.

“Our lighting levels are a fraction of what you might see at a concert, or the lights might be so bright they blind the audience, but on the video monitor it’ll look fantastic,” says Mitz.

“That’s the challenge when you’re lighting for both television and live.”

While the broadcast has to be the primary concern, one way to mitigate the differences is to vary the key-light color between performances or other segments of the event, offering some useful dramatic contrast for the video viewer but also giving those in the venue a visual break.

“We balance color temperature for the camera, of course, but once that’s dialed in we have some flexibility in terms of color and intensity,” he explains.

“That’s where we can make the experience a better one for the audience, too,” by making subtle adjustments to these parameter without reaching the point where the cameras need to be rebalanced.

Awards shows like the Grammy Awards are at the top of the live event-production food chain, but they share most of their technical nuances with any other live event regardless of scale.

Even supermarket openings will use line-array sound systems, wireless microphones and multiple LED screens. They all face the same challenges — and benefit from shared solutions.